The Integrating Brain - From Chaos to Cohesion: How Adolescents Learn to Hold Complexity

Part Three in An Eight-Part Series in The Thriving School Brief

About This Series

Inside the Adolescent Mind is a multi-part series examining how adolescent brain development intersects with identity, learning, and school design.

In the articles ahead, we will explore how emotions shape behavior, how sleep and stress affect cognition, how belonging influences decision-making, and how experience drives growth across adolescence.

Throughout the series, we return to a shared inquiry:

How might we design school systems that align with how adolescents actually develop?

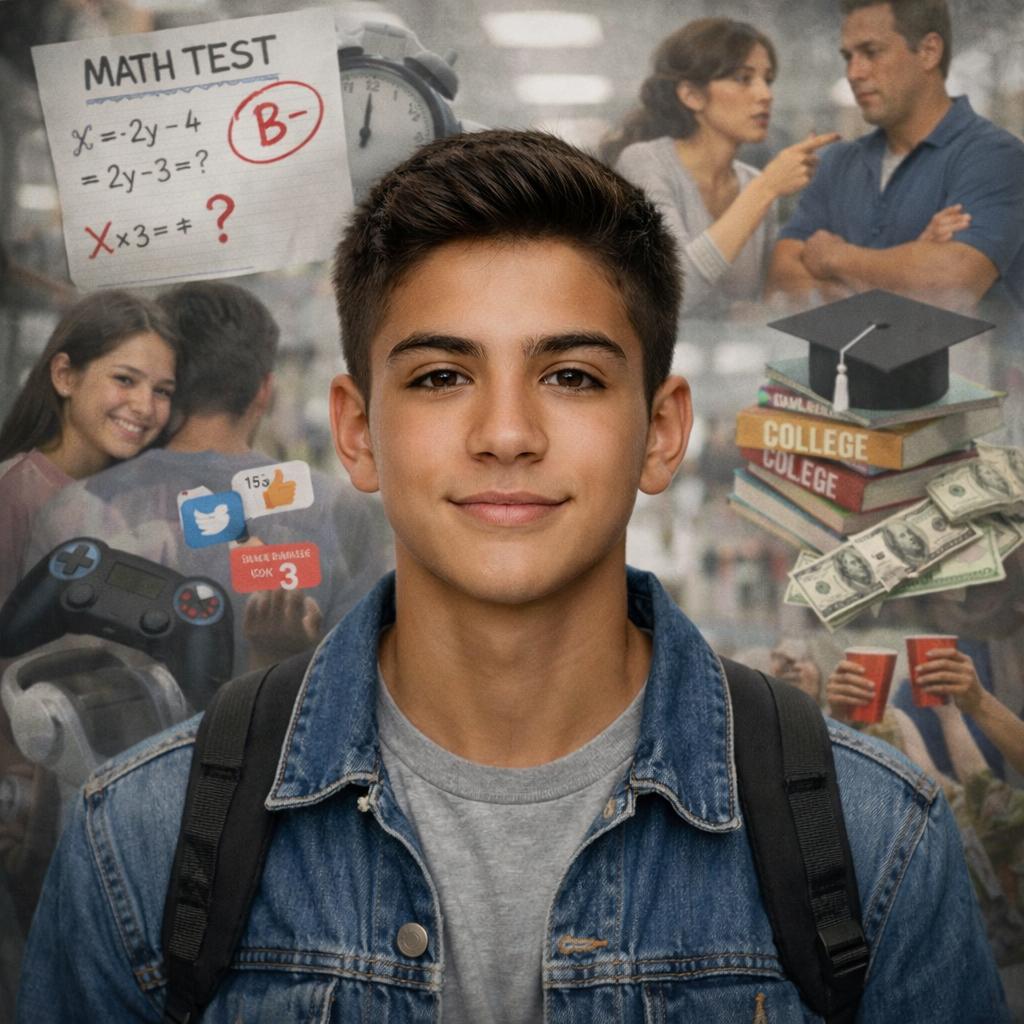

One of the most confusing things about adolescence is how uneven it can feel. Young people can be insightful one moment and impulsive the next. Deeply empathetic in one context and rigid or self-protective in another. Capable of reflection and still easily overwhelmed. From the outside, this can look like inconsistency or immaturity. From a developmental lens, it is often something else entirely.

During adolescence, young people are rapidly developing new capacities all at once:

stronger emotions

sharper opinions

a growing drive for independence

heightened social awareness

emerging and shifting identities

This growth is known as differentiation. The brain and sense of self are becoming more complex, with distinct parts beginning to take shape.

Integration is what links those parts together so they can operate as a coordinated whole. It is the process that connects emotion with thinking, impulse with reflection, self with others, and past experience with present choice.

When differentiation is happening faster than integration, adolescence can feel chaotic.

Young people may:

know what they “should” do but struggle to do it

feel intense emotions without yet being able to regulate them

hold strong opinions without nuance

shift between confidence and insecurity

act in ways that feel contradictory

Nothing is broken. The system just has not fully linked yet.

Put more simply: adolescents are rich in capacity, but still learning how to coordinate that capacity under pressure. This is not a failure of character or motivation. It is a developmental reality.

When we understand adolescent behavior as differentiation without integration, we stop interpreting inconsistency as defiance. We understand why knowing better does not always lead to doing better. And we begin to design classrooms and systems that support connection, reflection, and regulation rather than relying on control alone.

What can look like chaos from the outside is often development in progress.

Andrew, Before Integration

Andrew was an eighth grader with a lot of bravado. He did not like rules or being told what to do. He pushed back against teachers and structures and often found himself in trouble. From the outside, he could look defiant. From the inside, he was still figuring out where he fit and how much control he had in a system that often felt imposed.

I was Andrew’s advisor. We worked with him and his parents to make plans to support improvement. I no longer remember the specifics of those plans. What I do remember is that change did not come from a single strategy or consequence. It came through relationships.

Over time, Andrew began to shift. His behavior improved. His presence in class changed. He was not suddenly compliant or transformed, but he was more engaged, more reflective, more able to stay connected even when frustrated.

At the end of the year, when I gave awards to my advisory students, Andrew received Most Improved. At the time, it felt like a small recognition. One moment in a long year.

It turned out to matter far more than I understood.

What Is Physically Happening in the Integrating Brain

During adolescence, several major brain systems are undergoing rapid change at the same time.

Emotional processing centers, including the amygdala and other limbic structures, become highly sensitive and reactive. These regions are responsible for detecting threat, registering reward, and generating emotional intensity. At the same time, areas involved in social awareness and self-referential thinking are becoming more active, increasing adolescents’ attunement to peers, belonging, and status.

Meanwhile, the prefrontal cortex, which supports impulse control, perspective-taking, planning, and emotional regulation, is still in a prolonged process of maturation. It is not that these capacities are absent. They are present but less consistently available, especially under stress.

Integration is not about any single region maturing on its own. It is about the development of connections between regions.

Neuroscientifically, this happens through the strengthening of neural networks that link:

emotion-processing regions with regulatory regions

memory with present-moment decision-making

social awareness with self-reflection

impulse with inhibition

As these networks become more coordinated, information can move more fluidly across the brain. Emotional signals are more likely to be interpreted rather than acted on immediately. Past experiences can inform present choices. Multiple perspectives can be held at the same time.

This growing coordination is what creates coherence. Coherence means the brain can stay organized under pressure, allowing different systems to remain in communication rather than going offline or overpowering one another.

When Knowing Better Doesn’t Mean Doing Better

When integration is still developing, emotional intensity can temporarily overwhelm regulatory capacity. Under stress, adolescents may lose access to reflective thinking, language, or perspective, not because those capacities are gone, but because the pathways linking them are still strengthening.

This is why adolescents can demonstrate insight in one moment and struggle to access it in the next. The capacity exists, but the network is still under construction.

Importantly, these integrative pathways are shaped by experience. Repeated opportunities to pause, reflect, name emotion, repair relationships, and connect meaning across contexts help strengthen the neural connections that support coherence. Over time, the brain becomes more efficient at coordinating its parts.

Well-being, from this perspective, is not the absence of struggle. It is the capacity to move among different internal states without fragmenting, without losing access to thinking, connection, or choice when emotions rise or situations become complex.

When a system fragments, the parts stop communicating and start operating in isolation.

For adolescents, fragmentation can look like:

emotion taking over while thinking disappears

acting on impulse without reflection

one identity or feeling eclipsing all others

being unable to hold two truths at the same time

reacting as if the current moment is the only thing that exists

This is often the experience adults describe when they say a student “knows better” but cannot access that knowledge in the moment.

When integration is limited, adolescents may swing between extremes: shutdown or explosion, certainty or confusion, independence or dependence. When integration grows, those extremes begin to soften. Contradictions can coexist.

Andrew’s Moment of Meaning

The following fall, Andrew returned to school still in my advisory. Early in the year, I asked students to bring in something meaningful to them to share with the group. Objects varied widely: photos, notes, mementos.

When it was Andrew’s turn, he brought his Most Improved award from the previous year. He shared that it mattered to him because it was the first award he had ever received in school.

That moment was quiet. There was no grand speech or dramatic revelation. But something important was happening developmentally. Andrew was linking past and present.

He was integrating a history of struggle with a new narrative of possibility. He was holding pride without bravado. He was locating himself differently within the school community.

The award itself did not create that shift. The meaning Andrew made of it did.

Integration as Identity Work

Integration is deeply tied to identity formation. For adolescents, identity is not discovered all at once. It is assembled over time, through experiences that allow young people to connect who they were, who they are, and who they might become.

Andrew’s sharing reflected a growing capacity to see himself as someone who could improve. Not because he had become perfect, but because he could now hold effort and worth together.

This is integration.

Without opportunities to reflect, share, and make meaning, the brain may still change, but the story adolescents tell about themselves often remains fragmented.

When schools create space for reflection and connection, adolescents are more likely to integrate those experiences into a coherent sense of self.

What Integration Is Not

It is important to be clear about what integration is not.

Integration is not compliance.

It is not emotional suppression.

It is not constant calm.

It is not maturity arriving all at once.

A well-integrated adolescent still feels deeply. Still disagrees. Still tests boundaries. The difference is that they can increasingly stay connected to themselves and others while doing so.

When schools do not yet have a developmental lens, fragmentation is often misread.

Inconsistent behavior is interpreted as defiance. Emotional expression is labeled disrespect. Difficulty regulating is seen as a lack of effort or character.

In response, systems often default to what they know: tighter control, increased monitoring, and escalating consequences. These approaches can restore short-term order, but they rarely support the underlying developmental work adolescents are still doing.

When emotional intensity is treated as misbehavior rather than communication, adolescents are pushed to suppress rather than integrate what they are experiencing. The result is often more fragmentation, not less.

Understanding integration allows schools to shift from managing behavior to supporting coherence. It invites responses that help adolescents stay connected to thinking, language, and relationship even when emotions run high.

Integration grows when systems make space for complexity rather than trying to eliminate it.

What Classrooms That Support Integration Do Differently

Integration does not happen only inside the individual brain. It happens between people.

Dialogue, storytelling, and shared reflection help adolescents link emotion with language, experience with understanding, self with community. Being heard and seen allows different internal parts to come into conversation.

In Andrew’s case, sharing the award with peers mattered. His identity shift was not private. It was witnessed. This is why classrooms that support integration look relational by design. They prioritize conversation over compliance, meaning over monitoring.

Classrooms that support integration do not eliminate challenge. They scaffold coherence.

They offer:

structured dialogue where multiple perspectives are welcome

reflection practices that link experience, emotion, and learning

collaborative problem-solving that allows disagreement without disconnection

routines that invite students to make sense of their growth

Practices like dialogue circles, reflection journals, cross-curricular projects, and peer feedback are not add-ons. They are neurological supports. They help adolescents practice linking differentiated parts of themselves into a whole.

When School Systems Fragment Instead of Integrate

Schools rarely set out to fragment adolescents. Fragmentation emerges quietly, often as an unintended byproduct of systems designed for efficiency, uniformity, or control rather than development.

From a distance, fragmentation can look like a collection of unrelated problems: behavior concerns, motivation issues, attendance patterns, academic inconsistency, or escalating referrals. When viewed through a developmental lens, many of these patterns are connected.

Consider some common experiences school leaders notice:

Students who can articulate expectations clearly in a calm moment, but cannot access that understanding under stress.

Students whose behavior varies dramatically across classrooms, appearing regulated and engaged with some adults and dysregulated or withdrawn with others.

Students with strong cognitive skills whose emotional responses seem disproportionate to the situation.

Discipline referrals that cluster during transitions, unstructured time, or moments of public correction.

Students who comply outwardly but disengage inwardly, becoming quieter, more avoidant, or increasingly invisible.

These patterns are often interpreted as problems to fix in isolation. A developmental lens suggests something else may be happening. Adolescents are differentiating rapidly, but the systems around them are not consistently supporting integration.

When environments emphasize compliance over coherence, adolescents may learn to suppress emotion rather than integrate it. When reflection is absent, experiences remain disconnected from meaning. When relationships are transactional, identity work moves underground. The brain continues developing, but the opportunities to link emotion, thinking, identity, and belonging are limited.

Over time, this fragmentation can compound. Students may begin to experience school as a place where only certain parts of themselves are welcome. Other parts go offline. Behavior becomes less predictable, not because adolescents are choosing chaos, but because the system is not consistently helping them hold complexity.

This is often when schools see an increase in Tier 2 and Tier 3 supports, not because students are becoming more “broken,” but because Tier 1 environments are not fully aligned with the developmental work adolescents are doing.

Recognizing fragmentation at the systems level allows leaders to ask a different set of questions. Not, “Why are students behaving this way?” but, “Where might our systems be asking adolescents to manage complexity without enough support for integration?”

This shift does not lower expectations. It refines them. It invites schools to design environments that help adolescents practice coherence before expecting consistency.

Integration and MTSS Design

A developmental lens invites us to ask different questions of our systems.

Rather than asking why students are inconsistent, we ask where integration is being supported. Rather than responding to fragmentation with control, we design for connection.

At Tier 1, this means creating environments where:

identity is visible and valued

reflection is routine

relationships are central, not peripheral

growth is recognized over time

When these conditions are absent, fragmentation often shows up later as behavior referrals, disengagement, attendance concerns, or escalating Tier 2 and Tier 3 supports.

Andrew did not integrate his experience because of a program. He integrated it because the system allowed meaning to surface.

When MTSS is aligned with adolescent development, it becomes a framework for coherence rather than correction.

A Final Reflection

Adolescents are not meant to be simple.

They are becoming more complex, more differentiated, more aware of themselves and others. The work of integration is helping those pieces come together.

Andrew did not stop being himself. He learned to hold more of himself at once.

When schools design for integration, we do not reduce adolescents. We help them knit their experiences into something that makes sense.

And in doing so, we support not just achievement, but well-being.

Resources

Siegel, Daniel J. The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are. 3rd ed., Guilford Press, 2020.

Paus, Tomáš. “Mapping Brain Maturation and Cognitive Development during Adolescence.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences, vol. 9, no. 2, 2005, pp. 60–68.

Casey, B. J., et al. “The Adolescent Brain.” Developmental Review, vol. 28, no. 1, 2008, pp. 62–77.