The Pruning Brain - Use It or Lose It: How Adolescents Begin to Wire Who They Are Becoming

Part Two in An Eight-Part Series in The Thriving School Brief

About This Series

Inside the Adolescent Mind is a multi-part series examining how adolescent brain development intersects with identity, learning, and school design.

In the articles ahead, we will explore how habits form, how emotions shape behavior, how sleep and stress affect cognition, how belonging influences decision-making, and how experience drives growth across adolescence.

Throughout the series, we return to a shared inquiry:

How might we design school systems that align with how adolescents actually develop?

When I first started teaching, I believed that if I designed engaging lessons and maintained clear expectations, students would naturally respond with focus and motivation. I thought disengagement was something to fix and inconsistency was something to correct. I did not yet understand how much of what I was seeing was a reflection of adolescent development.

Years later, I would come to understand that adolescence is not a time of simple growth. It is a time of refinement. The adolescent brain is not adding endlessly. It is choosing.

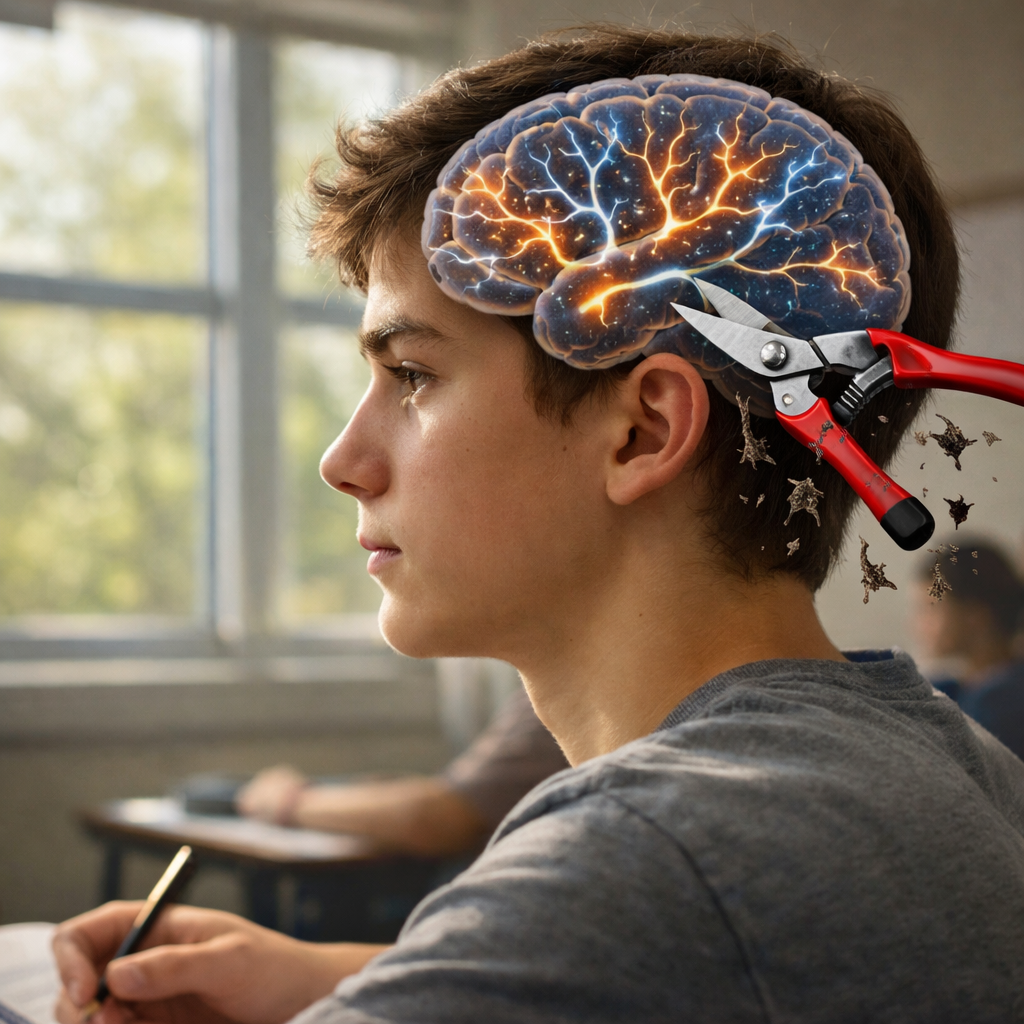

This process of choosing is what neuroscientists refer to as synaptic pruning. It is the brain’s way of deciding which connections to strengthen and which to let fade. But pruning is not simply a neurological event. It is deeply personal. It is how adolescents begin to shape identity, values, interests, and purpose.

Understanding this matters because many of the behaviors that frustrate educators are not signs of apathy or immaturity. They are signs of specialization in progress.

What Pruning Really Means in Adolescence

In early childhood, the brain grows rapidly and generously. Neural connections form in abundance, creating a brain that is flexible and open to many possibilities. During adolescence, that abundance begins to shift.

Connections that are used repeatedly are strengthened. Those that are not used are gradually trimmed away. This is not a loss of potential. It is a movement toward efficiency and depth.

From the outside, pruning can look confusing. Adolescents may become intensely focused on a narrow set of interests while disengaging from others. They may reject activities they once loved. They may seem restless in environments that once held their attention.

Internally, something else is happening. Adolescents are asking some of the most fundamental questions of human development:

Who am I becoming?

What matters enough to keep?

Pruning is how the brain begins to answer those questions.

A Story About What Adolescents Keep on Their Journey of Becoming

Several years after I had left the classroom, I received a call from a former student. He wanted to thank me for a class he had taken years earlier, a digital storytelling course that asked students to choose a story they wanted to tell, write a voice-over script, and pair it with images using a simple animation style.

At the time, I had thought of the assignment as a way to build communication skills and introduce multimedia tools. It was one of many courses offered within a school that valued creative expression and student voice. The structure was clear, but the content was open. Students chose the story they wanted to tell.

This student, Erick, created a digital story about meeting his grandfather for the first time during a trip back to Tanzania after immigrating to the United States. He reflected on the expectations his grandfather carried and the realities of his new life in America. The story explored belonging, cultural tension, and the quiet work of figuring out who he was across two worlds.

At the time, I did not think of this as a pivotal moment. It was simply one assignment among many. Years later, Erick shared that the experience had helped him understand himself in a new way. He had gone on to study film and storytelling, drawn by the same sense of meaning he had touched in that project.

What stands out to me now is not the assignment itself, but the conditions that made it possible. The course offered choice. It allowed depth. It treated identity as worthy of academic space. And it trusted adolescents with complexity.

That trust mattered.

Pruning as Identity Formation

Pruning does not happen in isolation from identity. In adolescence, the brain’s narrowing is closely linked to the work of becoming someone.

When adolescents are given opportunities to explore interests deeply, reflect on personal meaning, and connect learning to lived experience, the brain strengthens pathways that support purpose and agency.

When those opportunities are limited, pruning still occurs. Adolescents continue to refine their brains and identities, but the range of possibilities they can draw from is narrowed to what is immediately available to them.

This is why disengagement is such an important signal. Boredom, resistance, and withdrawal often indicate that the environment is not offering adolescents meaningful ways to invest their attention. The brain, faced with a lack of relevance, begins to look elsewhere for meaning, purpose, and agency.

This does not mean that adolescents should only do what they enjoy. It means that systems need to create places where interest, effort, and identity can intersect.

One way I often frame my work with adults is through a simple coaching question: If you are saying yes to this, what are you saying no to? And just as important, what will you say no to that makes this yes real and sustainable?

This is not just a leadership question. It is a developmental one.

The pruning brain is doing this work constantly. Adolescents are not only discovering what interests them. They are learning what they cannot hold onto if they want to go deeper. Time, energy, attention, and identity all have limits. Specialization requires letting go.

From the outside, this can look like loss. A student drops an activity they once loved. A young person pulls away from identities that once felt central. Interests narrow. Choices feel sharper. But from a developmental perspective, this is not withdrawal. It is discernment.

Pruning is the brain’s way of asking: What matters enough to keep?

And just as importantly: What can I no longer be if I want to become something more defined?

When adults understand pruning this way, we stop reacting to what adolescents are leaving behind and begin paying closer attention to what they are choosing to invest in.

Common Misinterpretations of Pruning in Schools

Many school systems unintentionally work against the pruning process by misreading developmental signals.

When students lose interest in activities they once loved, adults may interpret this as a lack of perseverance rather than a shift in identity. When adolescents push back against rigid structures, systems may respond with increased control rather than increased clarity and choice. When students appear bored or restless, the response is often more monitoring instead of more meaning.

These responses are understandable. They are also misaligned with development.

Pruning requires opportunities for choice, exploration, and reflection. Without these, adolescents are left to navigate identity formation without guidance or support.

What Responsive Systems Do Differently

Schools that align with adolescent development do not abandon structure. They redesign it.

Responsive systems recognize that adolescents need:

opportunities to specialize and go deep

permission to let go of identities that no longer fit

structured choice that supports agency

environments that value belonging and contribution

consistent opportunities to reflect on who they are becoming

This shows up in tangible ways.

Advisory structures that prioritize identity exploration rather than task completion.

Elective pathways that are treated as core, not peripheral.

Project-based learning that allows students to connect content to purpose.

Assessment practices that value growth, not just performance.

One example of this kind of redesign comes from New Britain High School, where leaders reexamined their morning entry routine through a developmental lens. Rather than funneling all students into the same start-of-day experience, the school created a clear but flexible structure that offered students limited, purposeful choices based on their needs upon arrival, including quiet spaces for regulation and academic preparation, communal spaces for connection and breakfast, and more active spaces for movement and social energy. Adult supervision remained consistent, but the system shifted from unmanaged compliance to supported choice, resulting in reduced early-morning conflict and a calmer start to the day for both students and staff. You can learn more about how this system was designed and sustained in this podcast conversation and read a deeper reflection on the redesign process here.

When schools design to meet adolescent needs, behavior becomes more predictable because the system is doing more of the work. These are not add-ons. They are responses to core developmental needs.

Designing MTSS With Adolescent Development in Mind

If you pause for a moment and look across your school, what patterns are you noticing?

Are there students who once seemed engaged but now appear to be checking out?

Are there students pushing back against expectations that once felt manageable?

Are there pockets of creativity, curiosity, or passion that feel invisible or undervalued by the system?

When these patterns show up, it is tempting to ask what students are doing wrong or which supports need to be added. A developmental lens invites a different set of questions.

During adolescence, pruning is always happening. The brain is narrowing, specializing, and deciding what to keep. The question is not whether pruning will occur, but what the system makes available for adolescents to prune toward.

When schedules are rigid, pathways limited, and definitions of success narrow, adolescents still specialize. They simply do so within a constrained field of options. Over time, students may prune away parts of themselves that do not fit the system rather than discovering how their interests, identities, and strengths might belong within it.

This is often when we see disengagement, resistance, or withdrawal. Not because students lack motivation, but because the system has unintentionally narrowed the developmental possibilities in front of them.

For school leaders and MTSS teams, this creates an important design challenge.

Instead of asking, Why aren’t students meeting expectations?

What if we asked:

What developmental skills are students still building?

Where does our Tier 1 environment invite choice, depth, and identity exploration?

Where does it unintentionally restrict the range of experiences students can meaningfully invest in?

Here is a brief thought experiment you might try with your leadership team:

Imagine following a student through a typical day in your school.

Where are they offered opportunities to choose, specialize, or go deep?

Where are they invited to reflect on who they are becoming?

Where are their interests, cultures, and emerging identities visible and valued?

And where are decisions being made for them without explanation or agency?

Now imagine one small shift you could make at Tier 1. Not a new program, but a design adjustment.

Perhaps it is a change in how advisory time is used.

Perhaps it is expanding what counts as meaningful academic work.

Perhaps it is redesigning a daily routine that currently prioritizes compliance over regulation or belonging.

These are not cosmetic changes. They shape what adolescents practice, invest in, and ultimately strengthen.

When MTSS is designed with adolescent development in mind, it becomes a framework that supports becoming rather than correcting. It helps adults interpret behavior as information, see disengagement as a signal, and design environments that keep multiple developmental doors open long enough for students to walk through them with intention.

The work of pruning reminds us that adolescence is not a problem to manage. It is a process to support. And the systems we design quietly teach students which parts of themselves are welcome to grow. Pruning is shaped less by what adolescents are capable of, and more by what they are allowed to practice.

A Final Reflection

Adolescents are not broken. They are becoming.

The pruning brain is not a problem to manage. It is a process to support.

When schools align with how adolescents actually develop, we do more than improve outcomes. We create environments where young people can discover who they are and who they might become.

References

Siegel, Daniel J. Brainstorm: The Power and Purpose of the Teenage Brain. TarcherPerigee, 2013.

Steinberg, Laurence. Adolescence. 11th ed., McGraw-Hill Education, 2017.

Giedd, Jay N., et al. “Brain Development During Childhood and Adolescence: A Longitudinal MRI Study.” Nature Neuroscience, vol. 2, no. 10, 1999, pp. 861–863.